FAQs: The context for Aotearoa New Zealand

To achieve Aotearoa New Zealand’s climate targets, we need to understand where our emissions come from, our commitments, and our role in global climate action.

This page provides background information about climate change and climate action in Aotearoa New Zealand, including the sources of its emissions, its approach to reducing emissions, its national and international commitments, and its role in global climate action.

What are the emissions from Aotearoa New Zealand and where do they come from?

The Ministry for the Environment publishes the New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory annually, which outlines all human-induced greenhouse gas emissions in Aotearoa New Zealand. This interactive emissions tracker lets you explore data in the inventory: New Zealand's Interactive Emissions Tracker | Ministry for the Environment

What domestic emissions reduction target has Aotearoa New Zealand set?

The Climate Change Response Act sets out Aotearoa New Zealand's agreed greenhouse gas target, which was set to align with other countries efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Aotearoa New Zealand has a ‘split gas’ target for domestic emissions, which considers biogenic methane separately from all other greenhouse gases. This reflects the different impact that methane has compared with other greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide.

Find out more about the 2050 emissions reduction target.

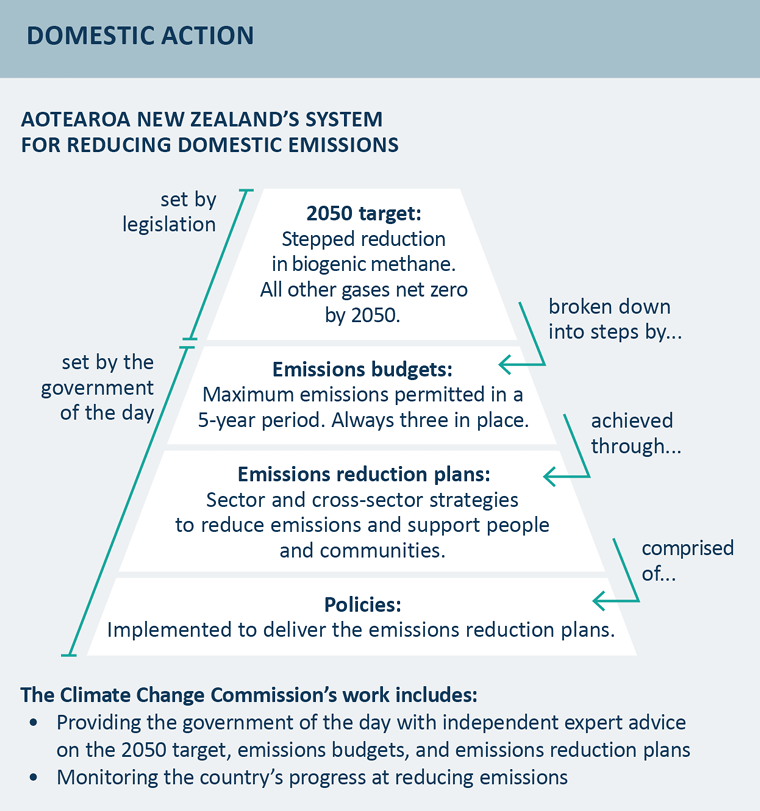

What is Aotearoa New Zealand’s system for reducing its domestic emissions?

Aotearoa New Zealand's system for reducing domestic emissions has four parts:

The 2050 target is the country's long-term goal, set by legislation and reviewed every five years. The target is:

- A stepped reduction in biogenic methane.

- All other gases net zero by 2050.

Emissions budgets are shorter-term goals to guide nearer term action, set by the government of the day. A budget sets the maximum emissions permitted in a 5-year period. There are always three budgets in place.

Emissions reduction plans are sector and cross-sector strategies set by the government of the day to achieve emissions budgets, and to support people and communities.

Policies are used to deliver the emissions reduction plans set by the government of the day.

The Climate Change Commission’s work includes providing the government of the day with independent, expert advice on the 2050 target, emissions budgets and emissions reduction plans.

We also monitor and review the Government’s progress towards its emissions reduction goals.

What international targets has Aotearoa New Zealand committed to?

Aotearoa New Zealand signed up to the Paris Agreement in 2016. The purpose of the Paris Agreement is to keep the global average temperature increase to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.

Under the Paris Agreement every country needs to set a nationally determined contribution (NDC). An NDC sets out what each country will do to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts. Each country is required to set successive, and progressively more ambitious, NDCs.

The NDC is different to the domestic emissions budget set under the Climate Change Response Act. It can be achieved through the actions we take here in Aotearoa New Zealand to reduce domestic emissions, and also by paying for emissions reductions overseas – for example through funding clean energy projects in other countries.

Aotearoa New Zealand submitted its first NDC (for the period 2021–2030) when it signed up to the Paris Agreement in 2016. This committed Aotearoa New Zealand to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. In October 2021, Aotearoa New Zealand updated this NDC to a target of a 50% reduction of net emissions below gross 2005 level by the year 2030.

In October 2023, the Minister of Climate Change asked the Commission to provide advice to help inform Aotearoa New Zealand’s second NDC, which must be set by 2025 and covers the period 2031–2035.

Find out more about our advice to the Government on NDCs.

What does ‘accounting’ for emissions removals mean and how do you do it?

All countries – including Aotearoa New Zealand – count the carbon removed by trees and use this to help balance the impact of greenhouse gas emissions.

To make sure the amount of emissions removed is fairly counted, there are internationally agreed rules and methods to ensure we are reporting credible and comparable data. These methods are provided by international climate change organisations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

How does climate action today affect Aotearoa New Zealand's future?

Our actions here in Aotearoa New Zealand matter. The climate is already changing, and communities across the country are feeling the impacts.

In every role we hold in our lives from business to community to home, we must all think about how every choice we make increases or decreases greenhouse gas emissions.

Over the next few years, the choices we make as individuals and as a country will determine how much impact climate change has on our future, and our descendants’. If current greenhouse gas emissions do not decline rapidly, we will be left with fewer choices for how we can act and react.

Aotearoa New Zealand has a global role as a food producer. What are the consequences of reducing our emissions in this area?

There is good reason to believe that production in Aotearoa will be competitive in a low-emissions future where meat and dairy products are still consumed.

Our analysis shows that the food and fibre sector can meet our recommended emissions budgets without significantly reducing production. To achieve this many of the 20,000 to 30,000 farm businesses across the country will need to change on-farm management practices to improve efficiency and some pastoral land will need to switch to forestry and horticulture and take up new technology as it becomes available.

Some farmers are already making these changes, and many more are working towards them.

Delaying action could affect the country’s trading position and businesses could lose market access as global markets are increasingly seeking low-emissions goods.

What climate change action is happening internationally and how does Aotearoa New Zealand fit in?

Limiting global warming requires a global effort. Each country needs to play its part by meeting its international climate change commitments to reduce emissions. Global ambition is increasing with many of the world’s largest emitters committing to strengthened climate targets.

The Paris Agreement includes a collective goal to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Each country is required to set successive, and progressively more ambitious, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) which outline their contribution to the global effort to limit the impacts of climate change.

The domestic emissions reduction targets for Aotearoa New Zealand are set at a level the Government has judged to be in line with contributing to global efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C. This is a requirement under the Climate Change Response Act (the Act).

While Aotearoa New Zealand has 0.06% of the world’s population, it emits 0.17% of all global emissions. That’s three times our share of the population. In addition, our gross emissions increased 19% between 1990 and 2021, whereas in many other OECD countries emissions are now below 1990 levels.

If you group the countries that individually produce less than 1% of global emissions together, they collectively contribute around a third of global emissions. Aotearoa New Zealand can be a role model by taking action that reassures others that they too, can take action.

What happens after 2050?

The emissions target is to 2050 and beyond. This means that after 2050, Aotearoa New Zealand needs to maintain net zero greenhouse gas emissions on an ongoing basis. The actions that we take now affect what we will need to do in the future.

For example, if rather than reducing gross emissions, trees are planted to absorb and store carbon dioxide, those trees will need to be maintained and re-planted if they are cut down (or lost to fire, flood or pests). Using trees rather than reducing emissions would also mean that more area would need to be planted with trees each and every year after 2050 to maintain net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

These sorts of considerations mean it is important that the actions taken now set the country up to meet and maintain the 2050 target in a way that create the best outcomes for current and future generations.

What other agencies are working on climate change?

Many organisations and communities are working to reduce greenhouse gases and/or adapt to the effects of climate change in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Deep South National Science Challenge

- Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority (EECA)

- NZ Environmental Management

- Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research

- Local Government New Zealand

- Ministry for the Environment

- Ministry of Primary Industries

- Motu Research

- National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA)

- New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute

- New Zealand Green Investment Finance (NZGIF)

- Royal Society Te Apārangi

- Stats NZ

Our related mahi

The Ministry for the Environment publishes the New Zealand Greenhouse Gas Inventory annually, which outlines all human-induced greenhouse gas emissions in New Zealand.

For example, they publish this interactive emissions tracker that lets you explore that data in New Zealand's Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

The Climate Change Response Act sets out Aotearoa New Zealand's agreed greenhouse gas targets. These targets are set to align with other countries efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Aotearoa New Zealand has what is called a split-gas emissions target. This means that there are separate targets for biogenic methane and for all other gases (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, F-gases and non-biogenic methane).

The first of the split-gas targets is to reduce biogenic methane emissions by at least 10% by 2030 and 24-47% by 2050 and beyond, compared to 2017 levels.

The second of these targets is to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, other than biogenic methane, to net zero by 2050 and beyond.

The Climate Change Response Act specifically excludes sanctions that trigger if New Zealand doesn’t meet emissions budgets or the 2050 goal.

Net zero refers to the balance between the amount of greenhouse gas produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere in a given period of time. The current target for New Zealand is that by 2050 the country has to remove as many greenhouse gases as it emits, over the year. Gross emissions, for example from aviation, may remain. They will need to be ‘removed’ or ‘offset‘ from the atmosphere, for example being absorbed by trees as they grow or through newer carbon removing technology.

Aotearoa signed up to the Paris Agreement in 2016. The purpose of the Paris Agreement is to keep the global average temperature well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.

Under the Paris Agreement every country needs to set a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). An NDC sets out what each country will do to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts. Each country is required to set successive, and progressively more ambitious, Nationally Determined Contributions.

New Zealand submitted its original NDC when it signed up to the Paris Agreement in 2016. This NDC committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

In October 2021, before the United Nations conference in Glasgow, New Zealand updated its NDC. The new NDC is a target of a 50 per cent reduction of net emissions below gross 2005 level by the year 2030. This can be achieved through the actions we take here in New Zealand to reduce emissions, and paying for emissions reductions overseas – for example through funding clean energy projects in other countries.

This target is different to the domestic emissions budget under the Climate Change Response Act.

You can read more here about the advice we provided to the Government on New Zealand’s NDC.

All countries – including New Zealand – count the carbon removed by trees and use this to help balance the impact of greenhouse gas emissions.

To make sure the amount of emissions removed is fairly counted, we all use internationally agreed rules and methods to ensure we are reporting credible and comparable data. International climate change organisations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) provide agreed methods for countries to use, and New Zealand follows these.

There is good reason to believe that production in Aotearoa will be competitive in a low-emissions future where meat and dairy products are still consumed. However, delayed action could affect the country’s trading position and businesses could lose market access as global markets increasingly seek low-emissions goods.

Our analysis shows that the food and fibre sector can meet our recommended emissions budgets without significantly reducing production. However, to achieve this many of the 20,000 to 30,000 farm businesses across the country will need to change on-farm management practices to improve efficiency and some pastoral land will need to switch to forestry and horticulture and take up new technology as it becomes available.

Some farmers are already making these changes. Many more are working towards them.

Limiting warming requires a global effort with each country playing its part by meeting its international climate change commitments to reduce emissions. Global ambition is increasing with many of the world’s largest emitters committing to strengthened climate targets.

The Paris Agreement includes a collective goal to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Each country is required to set successive, and progressively more ambitious, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) which outline their contribution to the global effort to limit the impacts of climate change.

The domestic emissions reduction targets for Aotearoa are set at a level the Government has judged to be in line with contributing to global efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C. This is a requirement under the Climate Change Response Act (the Act).

While New Zealand has 0.06% of the world’s population it emits 0.17% of all global emissions. That’s three times our share of the population. In addition, our gross emissions have increased since 1990, whereas in many other OECD countries emissions are now below 1990 levels.

If you group the countries that individually produce less than 1% of global emissions together, they collectively contribute around a third of global emissions. New Zealand can be a role model by taking action that reassures others that they too, can take action.

After 2050 New Zealand needs to maintain net zero greenhouse gas emissions on an ongoing basis. The actions that we take now affect what we need to do then.

For example, if trees are planted to store carbon dioxide, rather than reducing emissions, those trees will need to be maintained and re-planted if they are cut down. Using trees rather than reducing emissions would also mean that more area would need to be put into trees each and every year after 2050 to maintain net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

These sorts of considerations mean it is important that the plans put in place now set us up to meet and maintain the targets in a way that create the best outcomes for current and future generations/for us, our tamariki, and mokopuna.

The key principles for an emissions transition strategy and climate actions that can be sustained in the long term are as follows:

- Transition in an equitable and inclusive way

- Take a long-term view to 2050 and beyond

- Prioritise gross emissions reductions

- Create options and manage uncertainty

- Take a systems view.

- Avoid unnecessary cost

- Increase resilience and manage risks

- Leverage co-benefits.

Many organisations and communities are working to reduce greenhouse gases in Aotearoa.

- Ministry for the Environment

- Ministry of Primary Industries

- StatsNZ

- Environmental

- Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority

- National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

- Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua

- Royal Society Te Apārangi

- Deep South National Science Challenge

- New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute

- Oceans and Climate Change Research Centre

- Motu Research

- NZGIF